100th

MP

|

THE

100th

MONKEY

PRESS |

|

|

|

Limited Editions by Aleister Crowley & Victor B. Neuburg |

|

Bibliographies |

|

Download Texts

»

Aleister

Crowley

WANTED !!NEW!!

|

|

THE SWORD OF SONG |

|

»» Download Text «« |

Image Thumbnails |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Title: |

The Sword of Song. Called by Christians The Book of the Beast. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Variations: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Publisher: |

Society for the Propagation of Religious Truth (S.P.R.T.).1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Printer: |

Philippe Renouard, 19 , rue des Saints-Pères, 19, Paris.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Published At: |

Paris.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Date: |

August, 1904.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Edition: |

1st Edition. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pages: |

viii + xii + 196.5 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Price: |

Priced at ten shillings for state (b).1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Remarks: |

Apparently Crowley had planned to publish a popular edition of The Sword of Song as indicated in an S.P.R.T. catalog: ‘The Sword of Song. It is offered at cost price, in order to clear the first five editions in a month or so, to leave room for the popular editions at a still lower price, printed in a simpler form, and considerable condensed and abridged, this because much of the contents is of a very abstruse character, not suited for the mass of the people.’ Unfortunately, this publication never materialized.14

Dedicated to Bhikkhu Ananda Maitriya (Allan Bennett)2 Text printed in red and black.1 “Ascension Day” and “Pentecost” were written at Madura in 1901 on November 16th and 17th respectively.11 “Berashith”, originally titled “Crowleymas Day”, was written at Delhi on March 20 and 21, 1902.11 In keeping with Crowley’s interesting sense of humor, the initials of some of the hanging notes of ‘Ambrosi Magi Hortus Rosarum’ spell out the words “quim,” “arse,” “puss,” and “cunt.” ______________________________

It is said that Crowley sent a copy of The Sword of Song to everyone referenced in the book along with the following pro forma letter:10 (See example of the letter in images to the right)

Letters and Telegrams: BOLESKINE FOYERS is sufficient address. Bills, Writs, Summonses, etc.: CAMP XI, THE BALTOR GLACIER, BALTISTAN.

(or the feminine of any of these), as shown by underlining it,

Courtesy demands, in view of the

(c) homage to your grandeur (d) reference to your conduct (e) appeal to your better feelings on page _____ of my masterpiece, “The Sword of Song,” that I should send you a copy, as I do herewith, to give you an opportunity of defending yourself against my monstrous assertions, thanking me for the advertisement, or ––– in short, replying as may best seem to you to suit the case. I may add that there can be only one opinion as to part of your duty, i.e., you ought to subscribe to the Society for the Propagation of Religious Truth,* and thus aid its noble efforts to get a little sense into the average British or American brain. Your humble, obedient servant, ALEISTER CROWLEY.

* By whom "The Sword of Song" is published. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pagination:5 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contents: |

- Ascension Day - Pentecost - Berashith. - Science and Buddhism |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Author’s Working Versions: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other Known Editions: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bibliographic Sources: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Comments by Aleister Crowley: |

I had made a point from the beginning of making sure that my life as a Wanderer of the Waste should not cut me off from my family, the great men of the past. I got India-paper editions of Chaucer, Shakespeare and Browning; and, in default of India paper, the best editions of Atalanta in Calydon. Poems and Ballads (First Series), Shelley, Keats and The Kabbalah Unveiled. I caused all these to be bound in vellum, with ties. William Morris had re-introduced this type of binding in the hope of giving a mediaeval flavour to his publications. I adopted it as being the best protection for books against the elements. I carried these volumes everywhere, and even when my alleged waterproof rucksack was soaked through, my masterpieces remained intact. Let this explain why I should have been absorbed in Browning’s Christmas Eve and Easter Day at Tuticorin. I was criticizing it in the light of my experience in Dhyana, and the result was to give me the idea of answering Browning’s apology for Christianity by what was essentially a parody of his title and his style. My poem was to be called “Ascension Day and Pentecost”. I wrote “Ascension Day” at Madura on November 16th and “Pentecost” the day after; but my original idea gradually expanded. I elaborated the two poems from time to time, added “Berashith”—of which more anon—and finally “Science and Buddhism”, an essay on these subjects inspired by a comparative study of what I had learnt from Allan Bennett and the writings of Thomas Henry Huxley. These four elements made up the volume finally published under the title The Sword of Song. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Pages 256-257. ______________________________

The twentieth and twenty-first were great days in my life. I wrote an essay which I originally gave the title “Crowleymas Day” and published under the title “Berashith” in Paris by itself, incorporating it subsequently in The Sword of Song. The general idea is to eliminate the idea of infinity from our conception of the cosmos. It also shows the essential identity of Manichaeism (Christianity), Vedantism and Buddhism. Instead of explaining the universe as modifications of a unity, which itself needs explaining, I regard it as NOTHING, conceived as (illusory) pairs of contradictories. What we call a thought does not really exist at all by itself. It is merely half of nothing. I know that there are practical difficulties in accepting this, though it gets rid so nicely of a priori obstacles. However, the essay is packed with ideas, nearly all of which have proved extremely fertile, and it represents fairly enough the criticism of my genius upon the varied ideas which I had gathered since I first came to Asia. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Pages 275-276. ______________________________

One incident became immortal. I wrote in The Sword of Song that I “read Lévi and the Cryptic Coptic”, and lent the manuscript to my fiancé, who was sitting for Gerald Kelly. During the pose she asked him what Coptic meant. “The language spoken by the ancient Copts,” replied Kelly and redoubled his aesthetic ardours. A long pause—then she asked, “What does cryptic mean?” “The language spoken by the ancient Crypts,” roared the rapin and abandoned hope of humanity. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Page 356. ______________________________

I had completed The Sword of song before I left Paris and left it to be printed with Philippe Renouard, one of the best men in Paris. I intended to issue it privately. I had no longer any ideas about the “best publisher”. I felt in a dull way that it was a sort of duty to make my work accessible to humanity; but I had no idea of reaping profit or fame thereby. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Page 359. ______________________________

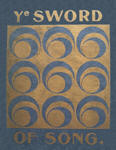

I have never lost sight of the fact that I was in some sense or other The Beast 666. There is a mocking reference to it in “Ascension Day”, lines 98 to 111. The Sword of Song bears the sub-title “called by Christians the Book of the Beast”. The wrapper of the original edition has on the front a square of nine sixes and the back another square of sixteen Hebrew letters, being a (very clumsy) transliteration of my name so that its numerical value should be 666. When I went to Russia to learn the language for the Diplomatic Service, my mother half believed that I had “gone to see God and Magog” (who were supposed to be Russian giants) in order to arrange the date of the Battle of Armageddon. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Page 387. ______________________________

My activities as a publisher were at this time remarkable. I had issued The God-Eater and The Star & the Garter through Charles Watts & Co. of the Rationalist Press Association, but there was still no such demand for my books as to indicate that I had touched the great heart of the British public. I decided that it would save trouble to publish them myself. I decided to call myself the Society for the Propagation of Religious Truth, and issued The Argonauts, The Sword of Song, the Book of the Goetia of Solomon the King, Why Jesus Wept, Oracles, Orpheus, Gargoyles and The Collected Works. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Page 406. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reviews: |

With references to my article last week I have received further

reproaches, but in nearly every case the letter divides itself

into two parts; first, a series of fiery taunts at my confession

of “abysmal ignorance,” and second, a more solemn remonstrance

with me for my “lack of charity.” Now I think this places me in

a somewhat pathetic position. I am not prepared adequately to

define charity, or any other purely mystical virtue. But I

should have thought that charity might, roughly, be described as

being “a confession of abysmal ignorance”—about abysmal things.

The only quite abysmal things are human beings. Charity might, I

think, be called an attitude of reverent agnosticism towards the

individual soul. If I said that a Jap loved nothing but evil in

his heart I should be uncharitable; I should be equally

uncharitable if I said it about Mr. Harry Marks. But I cannot

conceive in what possible way this charity can have anything to

do with our political sympathies or our favourite causes. For

this charity is due to all men: therefore, it cannot involve

wishing success to the Japanese. Unless it also involves wishing

success to the Russians. There are, I think, three classes of people who are annoyed with Mr. Hales and myself for feeling a philosophical or ethical distrust of Japan. The first class are the jelly people who simply have an idea that Japan is a little thing tackling a big one. To these people I have only to say that I drink to their healths. Their sentiment is quite irrational; it is quite right; and it is, moreover, peculiarly European and decidedly mediaeval. I would only remind them that hitherto in the field of war Japan has been the large Power and Russia the small one. The second class of people are those with whom I have hitherto been arguing. They hold something like this, as far as I can make out. They think that all men have by the light of Nature a certain scheme of morality, and that this scheme of morality is the Ten Commandments as understood in West Kensington. This covers the whole earth. Then on top of that come a number of fussy people with religions who want them, for no reason in particular, to believe in the oracle of Delphi, of the Wheel of the Buddhists, or the coming of the Messiah. These religions, they think, have nothing to do with ethics, and, apparently, do not even affect them. Men’s religion may be anything; they may be worshipping Christ or Silenus, or a crocodile, or the stars, or nothing at all, but if you go to their conduct you will find it the same as that of an American Ethical Society. This, I say, is unhistorical nonsense. Almost every moral code differs, not in its first moral need, perhaps, but in very important matters—in its view of monogamy, wine, suicide, slavery, caste, dueling, decency, the limits of endurance, the seat of authority. And nearly every moral code on earth arose from a religion, even if some of its followers have dropped the religion out of it. If a high-minded and pious Turk (of whom there are a great many) were to see Mr. Blatchford, say, addressing an American Ethical society, he would, feeling his own traditions on monogamy, wine, suicide, etc., say with perfect truth, “This is a sect of Protestant Christians.” But there is a third class of the passionately Pro-Japanese. The first class are those who sympathise with Japan through a chivalry towards small nations: that is, they love an Eastern people for a Western reason. I drink their healths again. The second class consists of those who do not admit that reasons are Eastern or Western at all. They say that religion does not matter. But the third class consists of those who think that religion does matter very much, but who do honestly prefer Buddhism—or, perhaps, Islam or Confucianism—to Christianity. They feel there is a Western and an Eastern philosophy; but they like the Eastern philosophy. To them it is idle to say that Orientalism may contain pessimism: for they are already pessimists. To them it is useless to say that it may undermine the Christian idea of free-will or the Christian idea of marriage, for they do not believe either in free-will or in marriage. Their position is perfectly clear and honest; but it is not any more tolerant than mine. For they are only (with a superb effort) tolerating the things they agree with. Among these are a great number of my correspondents: but they do not know it. Among these is Mr. Aleister Crowley; but he does know it. He publishes a work, “The Sword of Song: Called by Christians ‘The Book of the Beast,’ ” and called, I am ashamed to say, “Ye Sword of Song” on the cover, by some singularly uneducated man. Mr. Aleister Crowley has always been, in my opinion, a good poet; his “Soul of Osiris,” written during an Egyptian mood, was better poetry than this Browningesque rhapsody in a Buddhist mood; but this also, though very affected, is very interesting. But the main fact about it is that it is the expression of a man who has really found Buddhism more satisfactory than Christianity. Mr. Crowley begins his poem, I believe, with an earnest intention to explain the beauty of the Buddhist philosophy; he knows a great deal about it; he believes in it. But as he went on writing one thing became stronger and stronger in his soul—the living hatred of Christianity. Before he has finished he has descended to the babyish: difficulties” of the Hall of Science—things about “the plain words of your sacred books,” things about “the panacea of belief”—things, in short, at which any philosophical Hindoo would roll about with laughter. Does Mr. Crowley suppose that Buddhists do not feel the poetical nature of the books of a religion? Does he suppose that they do not realise the immense importance of believing the truth? But Mr. Crowley has got something into his soul stronger even than the beautiful passion of the man who believes in Buddhism; he has the passion of the man who does not believe in Christianity. He adds one more testimony to the endless series of testimonies to the fascination and vitality of the faith. For some mysterious reason no man can contrive to be agnostic about Christianity. He always tries to prove something about it—that it is unphilosophical or immoral or disastrous—which is not true. He can never say simply that it does not convince him—which is true. A casual carpenter wandered about a string of villages, and suddenly a horde of rich men and sceptics and Sadducees and respectable persons rushed at him and nailed him up like vermin; then people saw that he was a god. He had proved that he was not a common man, for he was murdered. And ever since his creed has proved that it is not a common hypothesis, for it is hated. Next week I hope to make a fuller study of Mr. Crowley’s interpretation of Buddhism, for I have not room for it in this column today. Suffice it for the moment to say that if this be indeed a true interpretation of the creed, as it is certainly a capable one, I need go no further than its pages for examples of how a change of abstract belief might break a civilization to pieces. Under the influence of this book earnest modern philosophers may, I think, begin to perceive the outlines of two vast and mystical philosophies, which if they were subtly and slowly worked out in two continents through many centuries, might possibly, under special circumstances, make the East and West almost as different as they really are. —The Daily News, G. K. Chesterton, 24 September 1904. ______________________________

Mr. Crowley’s poetry, if such it may be called, is not serious, at any rate, in its form. It is more colloquia, than the Ingoldsby Legends, and his matter, or rather his way of expressing it, is distinctly, though quite needlessly, calculated to irritate, not only the Christians to whom it is directly addressed, but even every serious-minded man of any religion whatsoever. . . . And yet Mr. Crowley’s book shows wide reading. If the form and tone of his work prevent his being read, Mr. Crowley will only have himself to thank. —The Yorkshire Post, date unknown. ______________________________

The Sword of Song, called by Christians the Book of the Beast. By Aleister Crowley. 10s. Society for the Propagation of Religious Truth, Benares. The most remarkable thing about this volume is the luxury of its material appointment—thick, glazed paper, head-lines and side notes on every page printed in red, while the main body of the book, verse and prose, is in handsome black. This is always something, but it handicaps the poet, and a reader naturally expects something tremendously fine in the way of afflatus to fill all this typographic sail. Well, the poetry here is disappointing. It is not so much that it is absolutely unintelligible; for a poet may talk consummate nonsense, if only he do charm; but the truth is, it is metaphysical, mystical, not to say esoteric; and (to make no bones about it) dull. The one idea of both the verse and the prose essays in the appendix seems to be to discredit Christianity and exalt Buddhism. But when the author annotates one of his lines thus—“This and the next sentence have nineteen distinct meanings,” and the reader is not able to make out any of the same, it is almost twenty to one he won’t enjoy the book. Sometimes the rhyme and the rhythm suggest an imitation of Browning; but, so far as the thought is concerned, Browning, in comparison with this author, is positively pellucid. —The Scotsman, 17 October 1904. ______________________________

Ye Sword of Song, by Aleister Crowley (Society for the Propagation of Religious Truth, Benares), is appropriately dedicated to fools. The plan of the poem is described as "Conspuez Dieu." It is a jumble of cheap profanity, with clever handling of metre and rhyme. Christianity will survive—but the author's reputation may not be so fortunate.. — The St. Jame’s Gazette, 20 January 1905. ______________________________

“The Sword of Song” is a masterpiece of learning and satire. In light and quaint or graceful verse all philosophical systems are discussed and dismissed. The second part of the book, written in prose, deals with possible means of research, so that we may progress from the unsatisfactory state of the sceptic to a real knowledge, founded on scientific method and basis, of the spiritual facts of the Universe. It is not easy to review Mr. Crowley. One of the most brilliant of contemporary writers. . . . Mr. Crowley’s short poems in particular reveal the possession of a beautiful and genuine vein of poetry, which, like the precious metals, is at times scarcely discernible among the rugged quartz in which it is embedded. With a true poetic feeling allied to remarkable learning, and with a pretty with of his own, Mr. Crowley is well equipped for producing a work of permanent value. . . . Good work may be found in “The Sword of Song,” but there is even more which will arouse in the average reader (to whom, however, Mr. Crowley obviously does not appeal) no other feeling than one of sheer bewilderment. Sometimes an oasis of beauty will reveal the author’s power to charm, the good-humoured egotism will tickle the fancy, the quaint allusiveness of the notes will raise the eyelid of wonder. . . . With regard to the prose portions of the volume, the essay on “Science and Buddhism” reveals some penetrating touches; but we have to confess that the discourse on “Ontology” baffles our comprehension. The poetical epilogue is beautiful and contenting. —The Literary Guide, date unknown. ______________________________

“The Star and the Garter,” by Aleister Crowley. - The poems of Aleister Crowley are “caviare to the general,” popular editions notwithstanding. “The Star and the Garter” is a peculiar dissertation on love, which, so far as we understand it, appears to be a justification of fleeting passions leading up to the “star” of a pure attachment, which, however, is in no wise injured by the lesser loves, symbolized by a “garter.” “Ye Sword of Song” (called by Christians “The Book of the Beast”) is full of erudition and satire. In it all religions are discussed and discredited, and a great agnostic conclusion is stated and proved. The second part of the book is written in prose, and “deals with possible means of research so that we may progress from the unsatisfactory state of a sceptic to a real knowledge founded on scientific method and basis of the spiritual facts of the Universe.” “The Star and the Garter” has been called “the greatest love poem of modem times,” and a scheme is on foot to furnish every free library, every workman’s club, every hotel, every reading-room in every English speaking country in the world with a copy of “Ye Sword of Song.” All particulars can be obtained from the Secretary S.P.R. T., Boleskine, Foyers, Inverness. —The Bath Chronicle, 24 November 1904. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||